On a muggy February afternoon in 1969, a US Army landing craft meandered down the Mekong River on a routine patrol mission. The boat was about a thousand yards away from the shore, safe from enemy AK fire – in theory. GIs scanned the treetops and bushes with their binoculars for Viet Cong, enduring the humidity and the quiet anxiety one can only get on patrol.

A Shot That Changed Optics Forever

The crack of a rifle in the distance broke the afternoon silence. A round pinged the side of the boat, and every soldier on board scrambled to find cover and return fire against the unseen enemy sniper. Another round struck the side of the landing craft. Nobody could find the shooter.

An American counter-sniper spotted the black-clad VC hiding among the leaves on top of a coconut tree, aimed his M21 and fired, taking out the enemy sniper in a single shot.

The American sniper was Sergeant Adelbert Waldron, who would go on to win two Distinguished Service Crosses for his outstanding skill and bravery. The legendary shot he made seemed impossible. He fired from a boat moving 2–4 knots (about 5mph) at a target 1000 yards away—just beyond the effective range of the M21.

The Leatherwood ART: A Technological Leap

The optic he used was a technological wonder for its time: the Leatherwood 3-9x Adjustable Range Telescope (ART). A brainchild of Second Lieutenant James Leatherwood, this riflescope was attached to a base which raised or lowered the scope according to elevation like an iron sight. All a sniper had to do was insert a target of known dimensions into a bracket on the ART’s reticle and adjust the scope’s cam until the target fit inside the bracket. The scope would automatically compensate for elevation. The magnification could also be quickly adjusted using a thumb-operated lever—long before such features became common. While the ART made rangefinding faster, it had a major drawback: it lost zero when transitioning between targets and had to be recalibrated each time.

Eastern Innovation: The Soviet PSO-1 Reticle

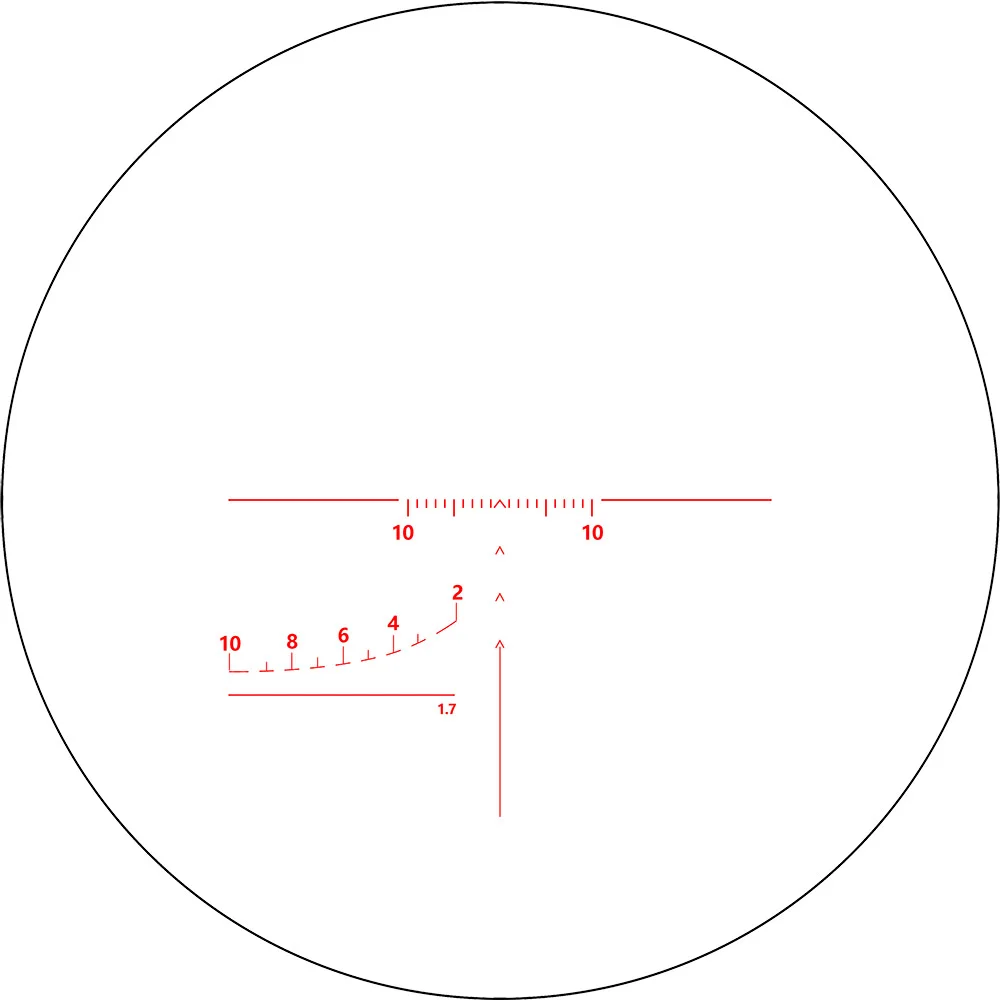

Back in those days, etched reticles were a rarity, and even high-tier brands like Leupold used simple cross reticles with small variations. In fact, at the time, the Soviet PSO-1 scopes the Viet Cong were using featured a more advanced reticle than nearly anything in the West. Used by Communist Bloc designated marksman rifles to this day, the PSO-1’s etched reticle allows for no-math ballistic calculations thanks to features like an etched integrated rangefinder. Located in the lower left corner of the reticle, this diagram allows the shooter to estimate the distance to a 5'7" tall target. It was also one of the first scopes to use a nitrogen-filled tube to prevent fogging.

Modern Riflescopes: Building on the Past

Fast-forward to the present, and we've not only caught up with Cold War-era technology—we've surpassed it. Today’s long-range optics frequently feature first focal plane (FFP) reticles, which simplify rangefinding without the need to adjust turrets mid-shot. For example, the Sightmark Presidio’s HDR2 reticle—designed for deer hunters rather than battlefield snipers—lets shooters estimate range based on target size without a calculator or cheat sheet, much like the PSO-1 but with modernized etched subtension lines and centered geometry.

Simple Math and MOA Subtensions

At 100 yards, 1 inch equals approximately 1 MOA. Using this knowledge, if a target is 10 inches tall but only fills half the distance to a 10 MOA subtension mark, the shooter can estimate that the target is around 200 yards away. The Presidio enables this kind of estimation at a glance, especially at higher magnifications, without compromising zero.

Old Meets New: The Return of the Throw Lever

As a nod to the ART’s original thumb-operated cam, the Presidio also includes a modern throw lever for rapid magnification adjustments—a feature that’s made a comeback in recent years after being replaced for a time by dial-only designs.

The Legacy of Innovation

Today’s riflescopes, like the Presidio, have borrowed the best from Cold War-era innovations while solving many of their limitations. Nitrogen-filled tubes, illuminated reticles, and FFP range-estimating systems now come standard on quality scopes. Unlike the ART, modern optics don’t shift zero with every range update. Instead, they offer precision without compromise, blending legacy engineering with cutting-edge technology.

Conclusion: Evolution of the Riflescope

The history of the riflescope is one of continual evolution—from leather-and-brass range cams in Vietnam to multi-coated glass, etched reticles, and quick-dial throw levers that dominate the market today. In every shot taken through modern glass, the lessons and legacy of scopes like the ART and PSO-1 still echo downrange.